How does Physical Therapy help frozen shoulder?

- Eric Hanyak, PT, DPT

- Nov 1, 2020

- 3 min read

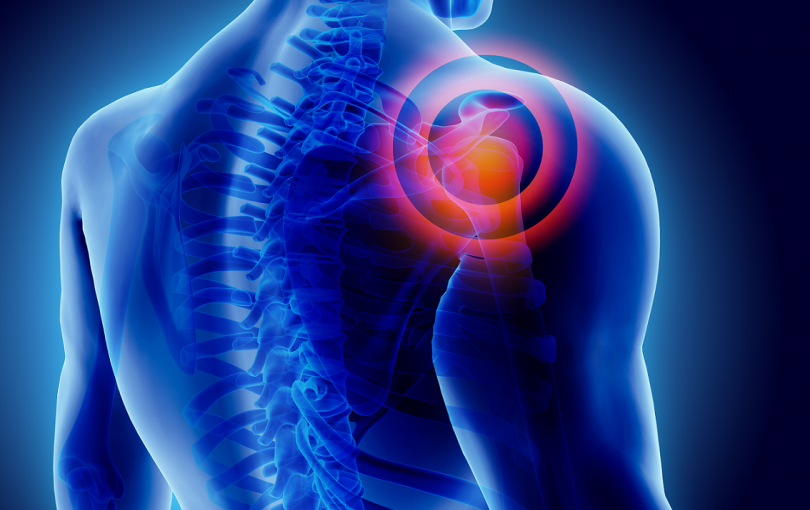

Frozen shoulder is a truly nagging and limiting condition that limits a person’s ability to move their shoulder, especially in a pain-free manner. If you’ve ever had it then you know how debilitating it can be. If you haven’t then hope that you will never have to deal with it.

Adhesive Capsulitis

Frozen shoulder, medically known as adhesive capsulitis, describes when a shoulder has painful and limited mobility due to the thickening and contracting of the capsule around the humeral head, or the “ball” of the “ball and socket” shoulder joint. (Imagine a belt being cinched tightly around the ball and socket). Risk factors include having diabetes, being between 45 and 65 years old, and being female. The symptoms can come on out-of-the-blue or often after some sort of preceding shoulder injury like a direct fall on the shoulder or a shoulder surgery. People who get it typically describe onset of shoulder pain followed by a loss of motion.

How long will this last?

One of the biggest problems with frozen shoulder is that it can last anywhere from one month to over two years! The variation in recovery can be extremely frustrating, especially in swimmers, tennis players, or other athletes who have an uncertain timeline for returning to their beloved activities. Despite this timeline, most people who get frozen shoulder have a good recovery, often even a full recovery to their baseline strength and range of motion.

Initially frozen shoulder may present like an acute shoulder strain, but one that doesn’t go away after a few weeks, it just gets worse. Often it goes undiagnosed for one to two months until a person no longer has the ability to lift their arm over their head and they finally seek medical attention. Even at this point it is often misdiagnosed as arthritis or rotator cuff strain. But once you get the correct diagnosis, what do you do about it?

Evidence based practice

The research across medicine and physical therapy is not conclusive on the exact course of intervention, but we have some indications on interventions to try. Studies show some pain relief from corticosteroid intervention and often this is a first line treatment with orthopedists. NSAIDs like aspirin or ibuprofen are often recommended for pain as well. Research in physical therapy suggests doing range-of-motion and strengthening exercises, joint mobilizations (a hands-on technique performed by the PT), and possibly TENS, ice, or heat for pain relief.

Having treated a frozen shoulder many times before I know that the body is going to go through its own healing timeline for adhesive capsulitis, but that PTs can improve the shoulder motion and reduce pain in a meaningful way. By starting with exercises for range of motion and strengthening we can start to improve shoulder motion and, at minimum, help prevent other muscles of the upper back from getting weak and starting issues of their own. Joint mobilizations to the ball-and-socket joint and the scapula (shoulder blade) can help to improve shoulder mobility. Initially these interventions may only help to reach a few inches higher into a cupboard, but after doing exercises for months and intermittent PT visits for hands-on therapy patients will start to return to their normal activities with more comfort and confidence.

While there is no magic bullet for treating frozen shoulder the combination of patience, physical therapy, and appropriate medical intervention can help to get people on the right road to recovery.

Comments